INTERVIEW: Justin Broadrick – Conclusion

by Diane "Lifer" Farris, March 16, 2021

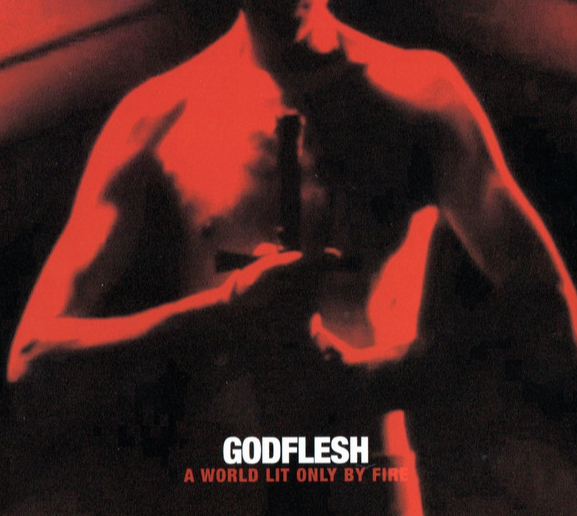

This is the transcription of my podcast from my WFMU radio show. You can listen here! This conversation with Justin Broadrick of Godflesh, Jesu, Final, etc., was in 2010, at the beginning of the return of Godflesh cycle after Justin really focused on Jesu, Final, Greymachine and other projects. This is the final installment of the interview. Check the podcast episode, or check out the entire 3 hour full radio special – complete with 100% Justin Broadrick/JK Flesh music. Either way, enjoy! Justin was a great interview! It’s cool to look back, and note that since this conversation there have been 2 Godflesh full lengths of original material released that hadn’t really even been addressed when we spoke. Support his work here!

DF: Do you go in with a certain discipline, or what kind of methodology do you use for yourself to stay on point and create as opposed to maybe getting distracted or, like you said going in with a blank canvas and coming out with a blank canvas.

JB: Yeah, that’s soul destroying, you know, because there’s nothing more I hate than being in the studio and not coming up with anything or just banging my head against the wall. And I’m not the sort of person who works at something, get frustrated and leaves it. I’ll keep going, so I’m my own worst enemy in a way. If I get frustrated -if I don’t reach anything then I’ll keep trying to reach it, as opposed to a lot of more sensible people than I, would just leave it there and then, but I keep coming back for more. You know, torture myself, but something may come of that but often doesn’t, I just have to have a very set idea and a lot of these ideas are born from just literal thought, or just listening to music and I do spend a good part of my day listening to other music, besides doing normal things like reading or browsing through art or watching films or whatever, which is all inspirational. I mean that from my life itself. Like I can have a walk in the country and get inspiration for a song or whatever.

Largely I’m going in with an idea that’s been embedded in my brain from the night before. It’s something I’ll develop in my head, quite literally, this can be from A to B all the way to Zed, then it’s just trying to interpret musically what I’ve had stewing in my head from the night before or the week before whatever really trying to chase that dream, to some extent. I find that when I imagine music it’s somewhat hallucinatory. I find it very, very dreamlike. And that for me is the magic of it; just like dreams, where they feel displaced yet centered at the same time, where there’s some sort of comfort in it, some sort of warmth, but it’s also alien as well. I find when I imagine, music, it’s that same somewhat hallucinatory surreal beyond -somewhat beyond reality, somewhere out there, and it’s then me trying to make that dream a reality and that’s how I generally look at music. I fail at trying to realize these dreams and that’s it for me. I’m always continually trying to realize these dreams and failing. (laughter) But the failure is part of it, for me it’s like that. That’s what it’s all about. It’s all- it’s all flawed. Everything I do is flawed. And it’s almost something by now at my age, and how long I’ve been working with music is something I’m proud of, I can wear this as a badge now. I can admit to it. As opposed to saying my records are perfect I think, on the contrary. They’re absolutely flawed from the bottom up. But I think in some way for me it’s potentially the beauty of my music -if there is any there is the fact that it is extremely human. And it recognizes itself. Trying to make dreams real is is a laborious unrealistic process really. Yeah, it’s not want of trying.

DF: Oh yeah, but the whole human condition is flawed.

JB: Yeah, exactly, which is, philosophically is something I’m exploring throughout my music anyway it’s something I’ve been quite clearly obsessed with since I was a child, imperfections, human imperfections and human frailty. The Human Condition. I’m obviously quite obsessed with it and self obsessed. You tell me any musician isn’t self obsessed. I just don’t think I’m that great. That’s the difference. Whereas I think some other musicians might think they are that great.

DF: I think that that’s part of your consistent way of pushing yourself and creating many many projects, and you haven’t done the same record twice ever.

JB: No. It’s constant dissatisfaction for me.

DF: Is it really?

JB: I mean absolutely if I finish a record, of course I’m proud of that record, even though I’m sitting there, nitpicking it, and generally by the time it’s released, which I think is probably universal that you’ve probably spoken to endless amounts of musicians who say by the time their record comes out. They’ve left it, it’s almost impossible to listen to. I think that’s fairly universal. I literally will rip that record to pieces. And I’ll be desperate to better it, you know what I mean. And I always think whatever I’m doing now is the best thing I’ve done. But then by the time I complete it, I’ll be annihilating it. I’ll be really unhappy with that record. So this is it, this is why I think, essentially is one of the reasons why I’m so prolific is I’m just never satisfied you know I’m just never happy with these records! Some may say, “well don’t release it then”, which is probably a fairly valid statement. But for me everything in music is exhibitionistic. How can it not be?

DF: So you’d said that you’re on top of all the latest gadgetry. You have to be really facile at using it in order to— if you’re trying to create “the dreamstate.” I guess I don’t see how there would be time to get hung up with “Wait, where’s that sound I’m trying to make,” so it seems like you’ve got hours and hours and, and years and years of really learning the technology, so that it can come out in the way that you want it to.

JB: Yeah, I mean, everything is a learning process for me. I get new equipment, and I literally put it into practice immediately. I mean of course I do sit there with manuals, but I’m sitting there being constructive as far as I’m concerned, anyway I’m immediately using this equipment. I can’t just sit there and tinker around, you know, it has to have meaning, even though I’m trying to learn equipment, or sitting there with a biblical amount of manuals, which is what it could turn into, this stuff. I’m not just a tech nerd, you know what I mean. And in fact, I’ve got no wish to just be a nerd who knows how to work these pieces of technology or whatever inside that, I approach the guitar in the same way I don’t consider myself at all that proficient a guitarist, I’m not in any traditional sense. I just took what I can, I’ve just pushed certain things out of the way and try and get to what I can. What’s in my head, but with a disregard for tradition somewhat, you know, because I can’t be bothered to learn the traditional way of doing things, I can only learn my own way of doing things – I think that’s what it is. Because that’s more exciting than trying to find out how other people do things or whatever or what is the traditional way of doing things. By doing that you one makes a lot of mistakes. But again, I think there’s a lot of beauty in mistakes in music.

DF: And that’s you saying that there’s mistakes.

JB: Of course, yeah entirely subjective it’s like to others. Sometimes I found songs or even entire albums I’m completely unhappy with, will be some of my most popular work! I think it often happens. This is it you can’t second guess anyone, so just so just work for oneself really ultimately.

DF: Yeah, that’s for sure. So you said that you do watch a lot of films, is there any movie that you would love to do soundtrack for.

JB: Wow, we could probably talk six hours alone about that sort of stuff. It’s almost impossible for me to summarize. I mean of course you watch certain movies that have stuck with me for years that were inspirational to pretty much all my music. I’m probably entirely satisfied with the way it works and I couldn’t even see myself spoiling it yeah. Some movies that you watch and musically they’re just perfect or sometimes the music doesn’t even enter into the equation. Yeah it’s almost, almost impossible for me to call that one.

DF: What’s one of the Godflesh records recorded in a bathroom?

JB: I think the the guitars and vocals were recorded in the bathroom in the house we were living in at the time, I think in the early 90s actually. That was when we first started getting our own equipment, I think because we first started getting our own equipment and didn’t have an allocated space, so to speak.

DF: So that was a poor man’s reverb?

JB: Yeah, absolutely. We were clutching at straws we were just learning through our mistakes. I know that I most certainly wanted to start producing our own records, wanting to get our own equipment. Instead of getting in and out of other people’s Studios which I found really dissatisfying. I always dreamt about my own studio even when I was about 10-11 years old. My stepfather had some really primitive equipment when I was a kid, and I used to love just tinkering with his equipment, I found it really exciting. The first time I ever went in commercial studios I found it a really nullifying experience; the environment, working with other people you’ve never met before in your life and, mostly having disagreeable personalities. These things are to me just obstacles. For me, making music and recording music is such an entirely personal thing that I don’t wish to be doing this with three people sitting around and accommodating their personalities and etc etc Yeah. The people from the studio or some tea boy on the side, some engineer, some managers and whatever. This is a personal experience for me it’s like all you people get out! You don’t even want to be looked at when you’re doing this stuff. I knew that the only route was to get our own equipment and to get our foot in the door of recording our own records. We’d have to take a lot of risks and we’d have to make a lot of mistakes. Even though the guitars we recorded in the bathroom were fantastic. I think it’s funny because the best record came out of that bathroom. It was was Slateman by Godflesh. That song is one of my favorite ever all time Godflesh songs, and that was where the bathroom legend came from: I recorded the guitars, and my vocals for that song in the bathroom in the house we were living in at the time. It’s one of the best sounding guitar tones I’ve ever committed to tape, oddly enough. That says it all, really.

DF: Yeah it does and in terms of experimentation and what you’ve done and I just want to thank you for putting yourself out there and experimenting and as you termed, “failing” over and over again to put forth the music that you have with Godflesh and Jesu and and all your projects, I want to recognize the extraordinary contribution that you’ve made to the world of music.

JB: Wow, I’m often humbled by you saying that a lot of stuff, I generally hear, I still don’t see myself in the equation, sometimes it’s still really really odd.

DF: Now you are in the equation. You are the front and center of that equation I mean when the first Godflesh record came out -first of all didn’t sound like there were any “mistakes”, it really blindsided a whole section of people who responded with, “Oh my god!” It didn’t take you guys a couple albums to get to your stride regardless of what you felt musically in your experimentation and that kind of thing. It was such a solid statement and really just blew away any, any standard that there was, and

JB: The self titled Godflesh album I guess you’re referring to not not Streetcleaner.

DF: You know, I think I heard Streetcleaner first.

JB: Yeah, as did most people. I mean those first two albums. They were recorded when we were so young as well. I was still a teenager, literally when those records were recorded so for me it was literally pushing it. They were extremely instinctive records; primal -atavistic almost – do you know what I mean? They were just not even recognizing anything. I could actually digress forever about those records but they are a sum of what I’d done previously. I guess we arrived at that via my years with Napalm Death and Head Of David, of course, without my experience and time with Head of David well, Godflesh wouldn’t have existed. So it was a snowball thing, but we hit it quick, with the sound, Yeah.

DF: Yeah, groundbreaking it’s not even the word. What do you want people to know about you. In closing?

JB: It’s a shame, but even now, I’ve really been saying this over 23-24 years of doing interviews, I am absolutely useless at closing comments.

DF: Okay.

JB: Besides expressing gratitude for every single person that even likes or buys my music in this day and age wow – mega gratitude for those who actually reach in their pocket and buy one of my records. Because you see record sales these days next to the amount that actually take your music for free and there are 20 times more people taking your music for free than those who buy it. It’s crazy -to even those who take it for free if they get something from it, then, who am I to argue? For me that’s all I can ever say really is I’m just absolutely grateful that I somehow have continued to have an audience for my music.

DF: We’re there for you! And really looking forward to whatever the next thing is, and thank you for being there for creating what you do! I think in a lot of ways because there’s not that many lyrics – not a lot of your projects are sing along able, there’s a whole lot of emotion that we’re allowed to express ourselves through listening to your music and that’s a huge part of the process. You know, you can listen to a love song and if it doesn’t fall exactly in step with what you’re going through you can sing with it but it’s not the same. Your music is open in that way, where it’s obviously really emotional, and it brings a lot of being able to get things out for a lot of people.

JB: Yeah, and that is pretty much what I’m here to do. I do feel that -by the time my music becomes public, that it IS for the public, then it was for me first and foremost. By the time it’s released, it’s for the world, and it’s for the world to appropriate it to their own lives. And it is exactly that- that’s why a lot of my stuff has been considered by many to be ambiguous, but I listen to music in the same way. We all interpret what we want from music. We take what we want individually. That for me is something I’ve tried to do, that is something I want to do; I want people to take what they want. And I’m not being dogmatic lyrically or anything, you know, it’s all, it’s all in the music.

DF: And that is completely understood. Yeah, thank you.

JB: No thank you!